I am an engineer by profession but I like to read about psychology and psychotherapy out of interest. As I have become familiar with it, I’ve found it to be highly logical.

I will specify the system first, and then use it to make some suggestions for our improvement.

I originally started writing this in July 2021 but it took several revisions before I felt it was polished enough to post.

The Self: A Systems Approach

Setup: Facts and Assumptions

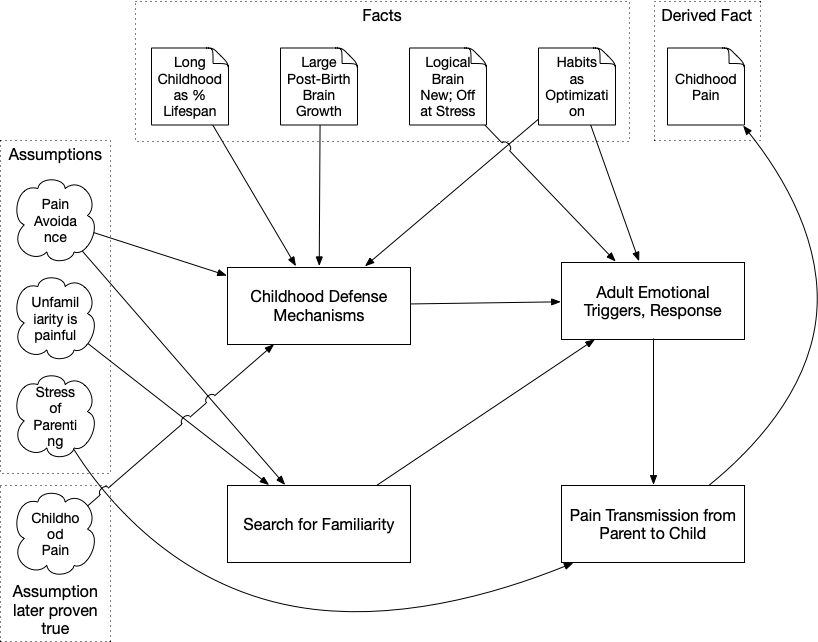

At the outset, let’s state a few undisputable, proven facts:

- We have long childhood relative to how long we live, within the animal world.

- Our logical brain is new, evolutionarily speaking. When under stress, it is not fully functional.

- Habits are an optimization to familiar stimuli that reduces processing power and lets things run on “auto-pilot”.

Next, let’s make a few assumptions:

- Let’s assume we don’t like pain and want to avoid it. We will later describe a variety of pain.

- Let’s also assume unfamiliarity is painful, or in other words, change is painful.

- Finally, let’s assume parenting is stressful, because by definition we are dealing with an emotionally unstable, tantrum-throwing non-grown-up.

Finally, let’s make one more assumption that I hope to prove correct later: that childhood is painful. I will not reason why, but let’s roll with it and see where it takes us.

Inference: Past in the Present

With this setup, we can make two inferences.

First, because we assumed that:

- we want to avoid pain, and

- childhood is painful

And because we know that:

- we have long childhoods,

- human brain is not logical when facing pain, and

- the brain forms habitual responses for familiar stimuli

We can conclude that:

A child will develop habitual, illogical patterns of response in order to cope with the specific pains it encountered repeatedly or acutely.

Second, because we assumed that unfamiliarity is painful,

we can conclude that an adult will seek familiarity.

Now, let’s combine the previous pain-avoiding child and grow him into a familiarity-seeking adult. As child, what is familiar to him is what he grew up in, for good or bad. As adult, how he responds to pain is what has become habitual to him in childhood.

This means when the adult faces pain or unfamiliarity, he will live the past in the present: his logical brain shuts down; instead, his primitive, habitual response and familiarity seeking will replay childhood reaction patterns.

Under duress, it’s as if our brain replaces the crucial question, “What is this?”, with “What am I familiar with that is very similar to what I’m seeing now?”. It then proceeds to react in the same way, causing a lot of second-order problems because it answered the wrong question. The saddest part is that the pain may even be as real as what the brain perceives it to be; it’s merely a function of how bad prior exposure was.

Inference: Automatic Propagation

Next we come to a crucial link. When this adult becomes a parent, he will continue to have such habitual reactions to the stress and unfamiliarity of relationships and parenting. When the child inevitably throws a tantrum or otherwise causes stress, his habitual pain-response kicks in. The child now gets exposed to pain, and he grows familiar with it throughout its long childhood.

We have thereby proven our initial assumption: childhood is painful, and pain is transmitted from generation to generation within a family and a tribe in an eerily systematic way.

We talked about a child and adult in the above argument, but we can extend it into many similar situations where you have initial long exposure followed by change: for example, if you stay long enough in your first workplace, starting again in a new workplace will bring the same forces to play, because you will see the new workplace with the lens of your past workplace. When selecting a spouse, he may look eerily similar to your parent (why?).

A Framework for Mental Well-Being

Is this all inevitable? It’s not hopeless. The system above also shows us ways in which we can break this vicious cycle. The facts are facts, but because we know how and when the components interact, we can find ways to improve our mental health.

Be Aware of Your Current Stress Level

A precondition to bad performance is that our brain is under stress. A situation appears more problematic if we go there already under stress. Here’s a checklist to gauge your stress level at any point in time:

- Are you healthy?

- Are you hungry?

- Did you get enough sleep last night?

- Are you tired, physically or mentally?

- Do you already have a problem you’re wrangling with in your head right now?

Being aware of your prior stress level can help calibrate your posterior stress level.

If possible, tackle a few things in the list above so that you can reduce your background stress.

Next, I give a few tips to deal with pain better.

Dealing With Pain

Know Common Defenses

There is a variety of common ways people deal with pain by not dealing with it. It is extremely useful to know these defense mechanisms. They will increase your awareness of how you might be lying to yourself. So as not to distract this post, I have listed them separately as an appendix.

Set Up a Process for Feedback

There’s no point in being hard on others when you’re under stress; you’ll probably overstate your case and irritate the other person. Instead, to reduce defensive behavior and promote meaningful change in you as well as others, set up a ritual for it.

In our family, we have a 15-minute “family meeting” time after dinner in the evenings. This is an idea borrowed from retrospectives in the agile software development framework. It’s not 100% perfect, but it allows time for feedback to be thoughtful and sets the expectation for everyone to lower defenses and be receptive to feedback. If something goes awry during the day, we know that we can bring it up in the evening, so the day goes smoothly. We also use this time to talk about our commitments and outlook for the next day.

Set Up a Time for Thought

Again, there’s no point fighting our habitual reactions during stress. Instead, you need to set up a time every day during which you do two things.

First, you think about what hurt or excited you during the day and how you reacted to it. What about that situation caused you pain or excitement? Was there a way you reacted to it that was a repetition from the past?

Second, you question any choices you made. Did you choose something because it made sense or because it was familiar to you? Did you like something because it was good or because it was familiar to you? What is becoming familiar to you now that may cause you to like it later? Did something change today that you didn’t see coming?

You can simply meditate about these when you take a shower, do the dishes or go for a walk, but if you have the time, writing your thoughts in a journal can be more helpful. If you do this long enough, you will see habitual patterns of behavior emerging.

A related activity, for extra credit, is to analyze your dreams. Dreams are usually about “wish fulfilment” and can be a window into your underlying emotional issues. The actual content of the dream is not so important as what you felt as you saw the dream.

Next, I will provide some guidance to deal with change and unfamiliarity.

Dealing With Unfamiliarity

Broaden Your Exposure

An anti-dote to familiarity-seeking is to regularly expose yourself to the unfamiliar: it could be unfamiliar places, people, cultures, times, situations or activities, but thoughtfully chosen under your control. Perhaps you can read a novel written by a foreign author coming from a different culture. Maybe you can try a different cuisine or fashion style. Learning a new language often exposes you to new ideas. If you have the money, you can try visiting a place in a different culture – or a different neighborhood in your city.

Reduce Surprises with Proactive Preparation

Familiarity-seeking is often our default response to surprise. It helps to know ahead of time what to expect, with proactive preparation, so that we can reduce the surprise factor. Perhaps you can observe more among older people in your family. You can read books that talk about common problems at different stages in life. You can watch great drama, or read literature. Similarly, you can find out what to expect if you’re getting a promotion at work, getting married, or becoming a father.

Transmitting Less Pain to the Next Generation

An awareness of your pain response can reduce how much you transmit your pain to your child. As additional help, expose your child to other people and cultures: extended family visits and stays, neighborhood activities, camps, foreign scholar exchange programs. This needs you to fight your protective impulse as a parent. You can also read kid-friendly books on mental health to your child, so that he has the vocabulary, knowledge and awareness of it.

Appendix: A Limited Catalog of Pain and Defense Mechanisms

Our pain and suffering comes in many forms. We may face rejection due to negligence, abandonment, criticism or humiliation. We may lack money to live a comfortable life. We may feel frustrated in many different ways: we may not have met someone else’s or our own expectations, faced injustice or shock. We may be anxious due to uncertainty about the future, or about lack of freedom or purpose. We may feel inadequate in many different ways: perhaps our body is not what we’d like it to be and it’s getting worse every year, our culture has a bad stereotype, or maybe our intelligence is not as good as a colleague’s. We may be heartbroken or in grief. We may be in front of a mountain of difficulties.

When faced with pain, we deceive ourselves in many different ways. It’s extremely useful to be aware of common defense mechanisms. We may deny outright that there’s a problem, so that we don’t have to confront it at all, even if that warps our worldview. We may run away from the problem, withdrawing into a shell or distracting ourselves with work or the Internet. We may displace our pain to a “punching bag” that happened to be in front of us at the wrong time. We may unknowingly bury or repress our pain because it’s so overwhelming. We may form reactions in a way that contradicts our true feelings, showering praise when we’re actually jealous. Like the fox, we may rationalize our unreachable grapes as sour with higher-order logic. We may compensate for our problem, asking our child to take up a career we failed in, or asking our partner to be our mother.